Written by Tom Flanagan | October 24

Tucked away on a quiet street in Walthamstow, a neighbourhood in the northeast of London, there’s a period house on the corner. It’s the home of Henry Miller, a lawyer turned art collector, and his partner. It’s also one of London’s largest galleries dedicated exclusively to homoerotic art and the male form.

“There are over 400 works on show throughout my home,” says Henry Miller, whose collection, spanning classical to contemporary art, is open for the public to visit on appointment.” He laughs. “My partner’s been incredibly patient with me, letting me decorate our home with every new work I find.”

Henry Miller in his home. Credits: ©Paultuckerstudio

Adorning every wall is some sketch of the male form; a fiery portrait of St Sebastien by Radek Husak, a picture of a naked man clutching his knees floating above the clouds, a sultry image of a young harlequin by Aldo Pagliacci. It’s a body of work that reflects Miller’s passion turned career and a culmination of an interest he’s had since he was a teenager.

“I started collecting [homoerotic art] when I was 17 when it was a very different time and pretty awful to be gay,” he explains. “My first piece was Andy Warhol’s Querelle. But for many, many years, I would trawl auction houses and sales and find nothing.”

The rise of homoerotica

That at least, seems to be changing, as a shift in demand for homoerotic art is unearthing a once obscured genre. Recent online data has shown there has been a surge in searches for homoerotic art in the past few years. As far back as 2015, the V+A Museum in London found that ‘homoerotic’ was one of its top 10 search terms.

On Catawiki alone, homoerotic art is among the most searched-for art terms on the site, with “homoerotic” showing a 175% increase from 2023 to 2024. Across social media, the demand for sensuous male visuals has led to an array of homoerotica-dedicated Instagram accounts (+2 million posts for #gayart) and even controversially, the rise of AI-generated men.

What’s driving this though? Well, a change in attitudes towards homosexuality and wider acceptance, for one thing, says Miller. “People used to care what their mother or friends might think of the art on their walls. But nowadays people come straight out with it, they don’t care. In fact, people are more prepared than ever to have more explicit things on their walls, which reflects the times we live in.”

This open embrace of homoerotic art marks a rapid shift in views compared to when it was seen as taboo. “In the past, interest in homoerotic art was limited to a small group of collectors, primarily from the gay community,” explains Catawiki’s Expert in Modern & Contemporary Art David Lopez-Carcedo. “It was largely kept hidden from society, with artists often working in secrecy or even facing accusations of criminal activity, particularly in the mid-20th century. However, since the 80s and 90s, interest has grown significantly, and today it extends far beyond just homosexual collectors. So while the interest itself isn’t new, the widespread appeal we see today certainly is.”

Left: Sensuality by Kasper Grzegorz Kasperek | Right: Henry Miller's home. Credits: ©Paultuckerstudio

Subtle sexuality

Yet for many artists and collectors of homoerotic art in the 20th century, there was a need for an alibi – another quality to these works like composition or scenery – to justify an interest in the art. It’s why a lot of homoerotica is more subtle than overtly explicit or sexual.

As an artist, you could paint a scene of two men naked by the water and if you called it German Romanticism then it was ok,” explains Miller, who notes sailors and horses as other devices used to signal homoerotic undertones. “There’s a great example of a Patrick Hennessey work called ‘Atlas Beach’. On the surface, it just looks like men on a beach in Tangier with the same name. But for those in the know, it captured men cruising above a gay club called Atlas Beach.”

The suspension of the imagination is one of homoerotica’s great qualities. The work of Michael Leonard (“wonderfully sexy and unerotic” says Miller) is an example of that, whose art embodied the idea of sexy in the suspension. And it’s these kinds of works that Lopez-Carcedo believes make for homoerotica’s enduring appeal.

“Homoerotic art shouldn't only evoke nudity or sexuality, but also convey ideas related to transgression or evoke something unimaginably twisted,” he says. “It's often subtle, and that's where much of its artistic value lies. It can be evocative or forbidden, though nowadays, very little is truly forbidden in this realm. The most sought-after pieces tend to align with what is more normatively accepted visually: highly idealised bodies and evocative scenes that engage the viewer’s imagination.”

Troubled history

Scandal has always followed homoerotica, no matter the medium; from classical paintings in Renaissance Florence – a city that set up a task force to deal with sodomy known as the Office of the Night – to modern-day mediums such as erotic magazines. João Florêncio, a professor at Linköping University in Sweden, has been studying homoeroticism in visual culture for years and says its re-emergence isn’t a new phenomenon.

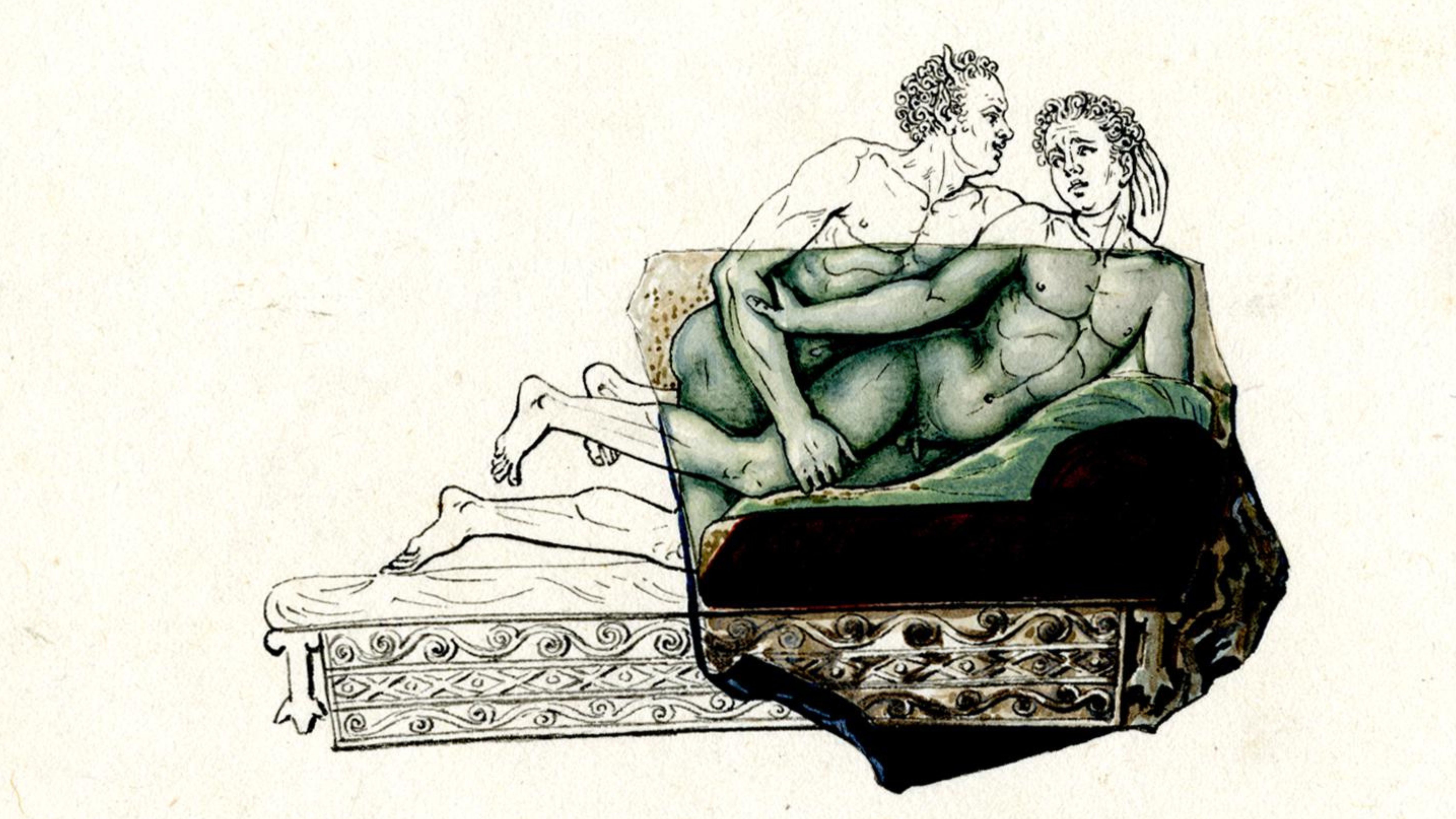

“Ever since the frescoes of Pompeii, images of homoeroticism have always been there,” explains Florêncio. “In classical Rome and pre-Christian times, they were a part of visual culture predominantly exchanged among men of the upper classes. During the Renaissance period, images of homoeroticism reemerged as Greco-Roman art regained appreciation, even when homosexuality was illegal. Pictures of deities were allowed because they were mythical – it was paintings of real people that were the problem. Eventually, anything homoerotic was “put away” because it was seen as dangerous to women and the working classes.”

Nude men in socks

Much of the art we now see as homoerotica was created at a time when it was dangerous to do so. And this context, in tandem with the rise of the internet, has allowed homoerotic art to take on a new purpose for collectors and perhaps explain why it’s increasingly sought out.

“Whether it’s classical paintings or zines today, these are objects of culture, a place of shared history for queer people,” explains Florêncio, who is also a long-time collector of analogue homoerotica. “The rise of the internet has made queer identity more homogenous – my partner and I joke about modern ‘gay art’ which is often just drawings of nude men in socks. But in classical times and the 20th century, there was less of a homogenous language and more of a sense of origin instead of repetition. These pieces have a kind of power you can’t describe. You feel they’re part of your history – and you collect them because you don’t want them to disappear.”

Homoerotic art has, like much of queer culture, relied on queer people to pass it on and it’s thanks to collectors like Miller and Florêncio the world will continue to access it. It’s something Miller also relates to; the power of works created at times when homosexuality was under threat and the kind of subculture they represent.

Henry Miller's home. Credits: ©Paultuckerstudio

“The older works still interest me because they were sneaky,” says Miller. “And there are so many artists like this that you can find now: early Hockney, John Minton, German artists like Sascha Schneider and Americans like Paul Cadmus. And of course, Tom of Finland.” Above all though, Miller says his desire to collect is fuelled by one thing: beauty.

“I’m drawn to things that are beautiful. I want beautiful things on my walls. I think that’s what all people want.”